There’s something quite satisfying in a historical sense about reading an Andre Norton novel based on Dungeons and Dragons and published in 1978, just four years after the game’s first box appeared in the world. It was so new that the novel uses the general term wargaming rather than calling it D&D as we would now. New, already expanding in popularity, but not the cultural icon that it’s become.

The world of fantasy wargaming, late Seventies style, is seriously in Norton’s wheelhouse.

Strongly plot-driven, powerfully dualistic (Light/Shadow, or here, Law/Chaos), meticulously worldbuilt, populated by a wide range of creatures both sentient and otherwise, constructed around a series of quests with an overarching goal and frequent disruptions by monsters and inimical magic—that’s Norton fantasy, notably the Witch World. The world of the novel is not specifically her world, but it feels as if she’s comfortable in it. It fits the kind of writer she is and the kinds of stories she likes to tell.

The story itself reminds me of the Magic books of the same era. Modern American gamer chooses or is chosen by a gaming miniature that serves as a portal into the world of the game. Parallel world, probably; she did love those. Gamer Martin becomes Swordsman Milo, and finds himself pulled into a fellowship with an assortment of other gamers transformed into their gaming selves. There’s a fairly standard mix: Berserker/wereboar, Druid, Bard, Elf Ranger, Amazon warrior-priestess, and a sort of odd man-thing out, a Lizard warrior. They’re quickly rounded up by a magic user of this world and compelled to go on a quest to find and destroy the alien power or creature who brought them here.

They travel through a fairly standard fantasy landscape, from a diverse city with distinctly seamy underbelly through open grassland to a range of forested mountains and then through the Sea of Dust to a dismal swamp that seems to have been grafted onto this world by the alien power. Each player has a set of predetermined weapons, spells, and powers, and all of them are bound by a bracelet equipped with jeweled dice that serve to both guide and control them. They’re here to play out the alien power’s game and also, apparently, to disrupt the spacetime continuum by combining this world and the alien world.

The wizard has done his best to disrupt this plot and give the gamers the wherewithal to resist the compulsion of the dice. They quickly learn to resist and even control their moves, though they can’t get rid of the bracelets. When they are presented with challenges, they prevail, assisted by the Druid’s healing powers and the various characters’ individual weapons, talents, and spells.

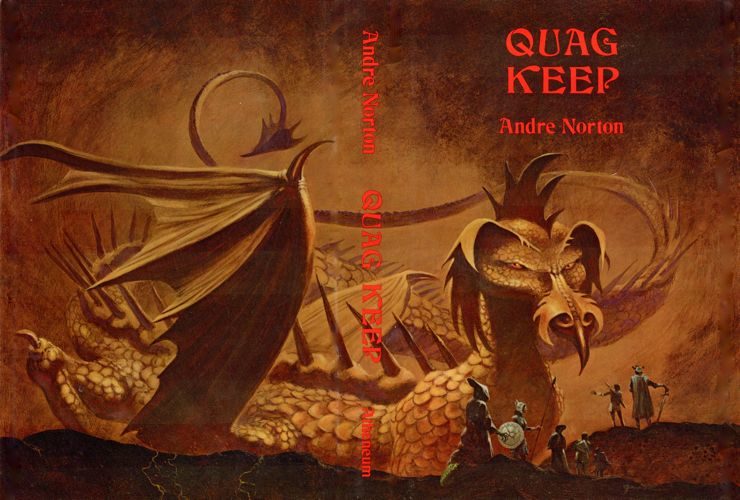

Challenges include some classic early D&D monsters, a Golden Dragon who mostly serves Law, a Brazen Dragon who serves Chaos, and an army of zombies, or as the game calls them, Liches. They have to keep an eye on their finances, food and water are a constant preoccupation, and their horses are carefully researched: they discuss what type to get (Milo excludes the fancy warhorse with great reluctance and determined practicality—it just will not do for a quest of unknown duration through unknown but probably rough country), buy extras in case any are lost along the way, and select tack and supplies with equal care and attention to detail.

This is fantasy with rivets as we used to say. Solidly based in practical reality, even with the so-convenient healing spells (and a plothole: we’re told the Druid can only use his foreseeing spell once and that’s it, but a few pages later, there it is, apparently as good as new). The quest winds to its end, leading to a human Dungeon Master who has discovered or been induced to discover a means of manufacturing gaming miniatures that enslave gamers to his will. The factory is about to go on line and take over the gaming world—and our heroes (and our token heroine) have to stop him.

It’s a very readable adventure, rapidly paced in patented Norton style. I particularly liked the Sea of Dust, the snowshoes they construct to travel across it (and the realistic physical strain of learning to walk in them), and the buried dust-ship that turns out to be full of Liches and also, conveniently, a large supply of magical healing wine. That was a new setting for me, both interesting and ingenious. Though I did wonder about lingering effects from breathing the dust. I guess the wine takes care of that.

The nature of the game fits Norton’s style and plotting preferences amazingly well. Here, when the plot drives a character, it’s built in to the world. Her propensity for having characters do things with no idea as to why, driven by outside powers who may or may not manifest in the narrative, makes sense here. These are gamers, and they’re playing a game controlled by others—both the wizard with his geas, and the Dungeon Master from another world.

I’m less happy with the way she handles the basic concept of the modern gamer turned into his (and one token her) character. It almost reads as if the idea isn’t hers, or as if she’s doing it as a marketing device. “Gamers want to know they’re in the game.”

But once the game gets going, she drops the dual-consciousness idea as early and often as possible. We never find out anything about most of the other gamers. I would love to know who is playing the Lizard warrior and how he manages to mesh his human self and the profoundly alien character. And what about the Elf? He’s quite alien as well.

Norton deliberately avoids getting beneath the surface of anyone but Martin/Milo, and every time Martin starts to emerge, he decides, nope, not a good idea, must go back to being all Milo. There are some practical considerations here—Milo knows the world, has the martial and survival skills, and needs to not be distracted while he’s trying to survive—but there’s a lot of missed opportunity. Just as the structure of the game plays to Norton’s strength as a plotter, the basic concept shows up her weakness as a writer of character. It’s all about gamers forced to become their characters, but she backs off from addressing any but the most basic ramifications. And then, at the end, nobody goes home, or much seems to want to.

That’s the Sequel Signal, of course. In fact there is one, published many years later, which happens to be a collaboration. Generally I try to stick to the solo novels, but this time I need to see where Norton was going with this. Will she or her coauthor fill in some of the holes? Will Martin and company find their way home? How will the dice roll for the next adventure?

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her most recent novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café and Canelo Press. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.